112 East Hennepin Ave, Minneapolis

612.379.2021

IT HAS BEEN JUST THREE MONTHS since Esquire declared Nye's Polonaise Room to be the best bar in America. The author of the story, a former sports writer from Toronto named Chris Jones, obviously greatly loves the St. Anthony institution. He meticulously researched the place, describing in great detail the bar's kitschy decor and antique staff. Jones drove himself into a frenzy of purple prose trying to find the right words to describe the place, coming up with an embarrassingly orchidaceous intro in the process. "The best bar in America occupies a corner where the path to righteousness and the road to perdition run parallel, east to west, perpendicular to the muddy river that cuts this country in two, north to south," Jones wrote, and it's a mouthful for a bar and restaurant that remains stubbornly charming, despite the fact that the bar is so thoroughly a nesting ground for slumming Yuppies and white-belted hipsters that it's nearly impossible to find a quiet spot to enjoy an overpriced drink.

Jones gets the details of the place right, mostly. But here's a Nye's story he didn't know, or neglected to tell.

Jones gets the details of the place right, mostly. But here's a Nye's story he didn't know, or neglected to tell.Back in 1972, Dayton's had a rather formidable art gallery called Gallery 12, which offered such upscale items as works by pop artist Tom Wesselmann and sculptures by Venezuelan artist Marisol, which even in 1968 were selling for $8,000. Gallery 12's curator was a fellow named John Stoller, and Stoller had an interest in a German artist who was then still somewhat unknown in the United Sates: Jospeh Beuys. The 51-year-old Beuys, a thin man with a long face and a taste for fishing vests and enormous Trilby hats, had a sizable reputation in Europe for producing highly symbolic and idiosyncratic work loosely affiliated with the Fluxus movement, such as 1965's "How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare." In this piece, Beuys put himself on display through the window of a Duesseldorf gallery, his face covered in gold paint, cradling a dead hare and explaining art to it.

Working with a New York art dealer named Ronald Feldman, Stoller arranged to bring Beuys to the United States on a speaking tour: The artist, over the course of 10 days, would lecture in New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis, appearing locally both at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and at the University of Minnesota. Beuys' lectures were sprawling and ambitious, and he illustrated them on chalkboards, dubbing his lectures "Energy Plan for the Western Man" and detailing his ideas for combining art, science, and religion in such a way that might restore the balance he saw lacking in the western world. In Minneapolis, Beuys replaced chalkboard with zinc printing plates, and his diagrams became a piece of art themselves, titled "Minneapolis Fragments." But it was not the only piece of art he created while in Minneapolis.

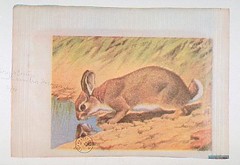

During his stay, Beuys was taken to Nye's Polonaise Room, and while he was eating, he noticed that the sugar packets in Nye's were printed with the image of a hare sipping water at a lakefront. The hare was a recurring image in Beuys' work -- he was impressed by the fact that the hare burrowed in the earth and emerged from it again, which, to the artist, symbolized death and rebirth. So, with the help of other diners, Beuys rounded up all the sugar packets at the bar. These he later marked with a self-fashioned stamp and exhibited as readymade art, in the manner of Marcel Duchamp, who was an early and important influence on the artist. These stamped sugar packets from Nye's formed a series named "American Hare Sugar," and can be found in the Tate and other important collections.

Most of the pleasures to be had at Nye's are joyously lowbrow, and Twin Citian's know them well: The World's Most Dangerous Polka Band, with Ruth Adams, the band's toothless accordion player; Sweet Lou, who leads the piano bar; the formica tables and glittery plastic booths. It's just what Chris Jones wrote about in Esquire, and it's exactly what locals love about the bar. But it's worth noting that Nye's contribution to the world hasn't just been kitsch: At least once in its history, the bar produced art. (SPARBER)

2 oz. whiskey

2 oz. whiskey

No comments:

Post a Comment